6 November 2019

Researchers find the first evidence in humans for increased plasticity in the auditory cortex as a result of early blindness or vision impairment.

In the absence of visual information, functional sensory areas in the brain, such as those responsible for hearing, develop enhanced capacities, making a blind person’s hearing more sensitive to subtle differences in frequency, reveals the study published Journal of Neuroscience.

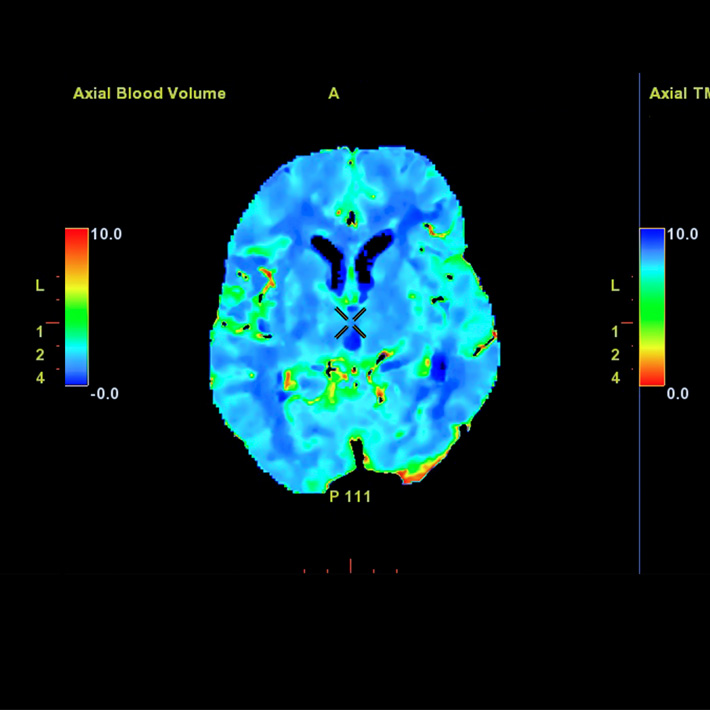

“A voxel is a chunk of brain only 3 by 3 by 3 millimetres, but it contains almost a hundred thousand neurons. For each of these tiny chunks of the brain, we looked to see what auditory frequencies they responded to,” says Ione Fine, professor of psychology at the University of Washington, and the study’s principal investigator.

Early blindness has generally been linked to sharper hearing.

This study, however, provides evidence that blind people are not just good at auditory tasks, but that their perception of the auditory world is slightly more refined. They’re better at tuning in to slight variations in sounds and at tracking moving objects by sound alone.

Fine and colleagues not only confirmed that people who were born blind or have become blind in childhood are better at making distinctions between two or more tones that are similar, but that these tones are also represented differently in the brain.

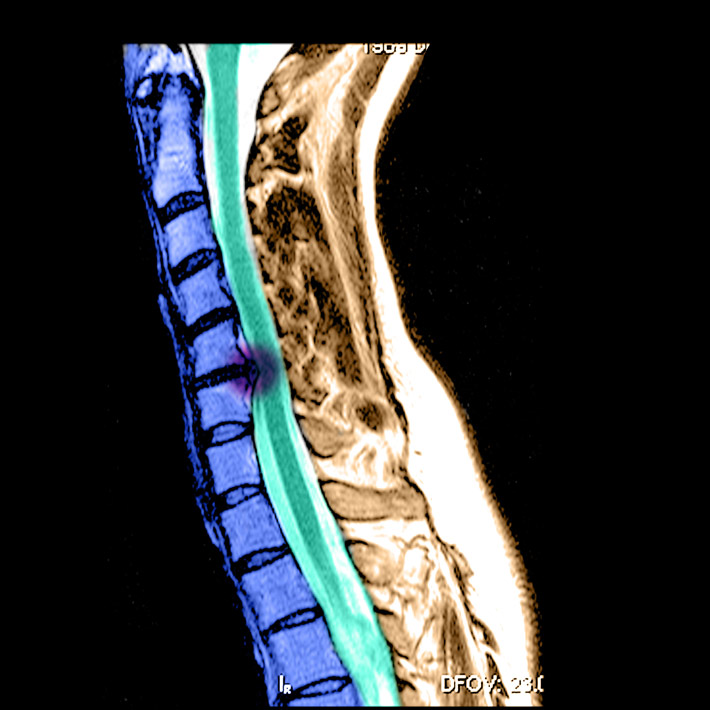

The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure how populations of neurons represent information about sound inside the brains of blind and sighted participants by detecting changes in blood flow and oxygen metabolism.

“Instead of just looking at whether responses are bigger or smaller, we really looked at how sophisticated that representation is,” Fine explains.

Their investigation showed that, in blind participants, the auditory cortex becomes better at extracting more information from sounds. This narrow frequency tuning is evidence of compensatory plasticity.

Fine says that this type of plasticity, where an area inside the brain becomes more responsive as a way to compensate for deprivation in another area, has so far been understudied. She explains that scientists were more fascinated by cross-modal plasticity, in which an area of the brain takes on new functions. “A brain area getting slightly better at doing its normal function is less dramatic,” she says.

The scientists plan on taking a deeper look. “Audition involves much more than pitch. It also involves things like timbre, tracking moving objects, and identifying objects from the sound they make. We’re interested in how blindness influences all these different tasks,” says Fine.

References

- Huber, E. et al. Early Blindness Shapes Cortical Representations of Auditory Frequency within Auditory Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience39 (26), 5143-5152 (2019) | article