1 December 2019

Fence lizards whose ancestors were frequently exposed to extreme stress tend to develop better immune responses to stress in early life, according to new research.

“When we think about how an organism responds to stress, we don’t always consider previous experience,” says Gail McCormick, first author of The Journal of Experimental Biology study, and biologist at Pennsylvania State University. “Our research reveals that an individual’s experience with stress in its lifetime, as well as its ancestors’ experience with stress, both play important roles in how the individual responds to it.”

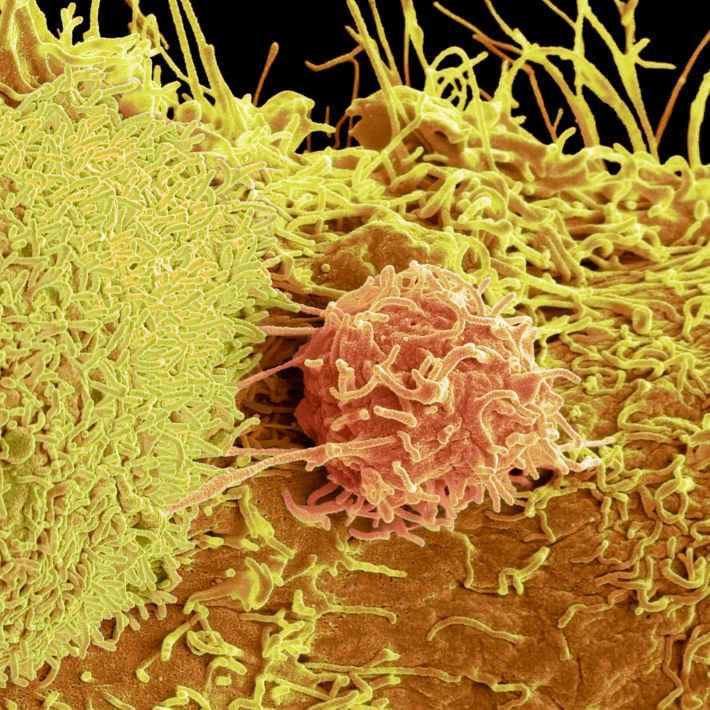

Animals typically react to stressors, including attacks from predators, through fight, flight or enhancing immune function to prepare for injury and trauma — the latter is the focus of the study led by Tracy Langkilde, head of biology at Penn State.

To study transgenerational stress and its implications on early development, McCormick and her colleagues experimented on Sceloporus Undulatus or eastern fence lizards, native to southeastern United States. As of the 1930s, these lizards often shared their habitat with fire ants, an invasive species that can sting and leave victims open to fatal infections.

For comparison, the researchers collected pregnant female lizards from both low-stress sites that are free of fire ants, and high-stress sites where the reptiles had been under attack for more than 30 generations.

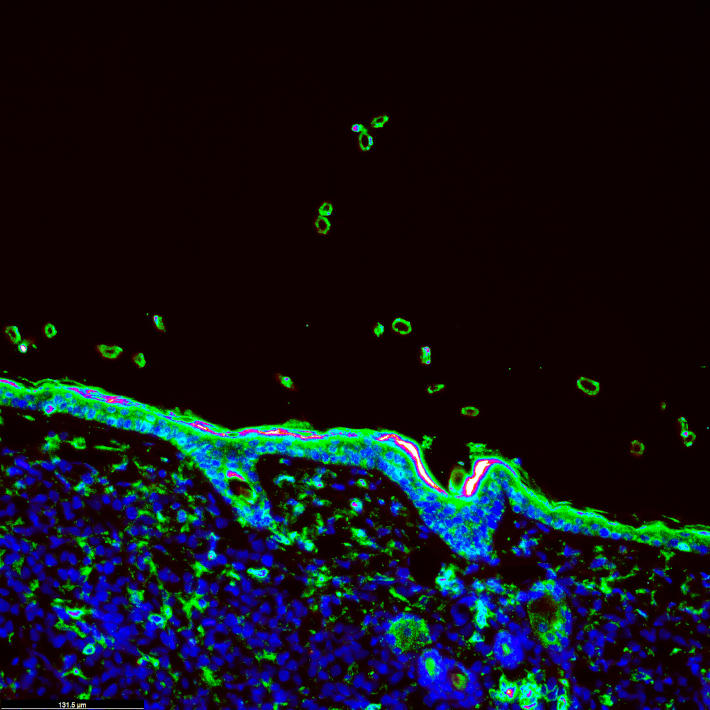

They raised offspring from these lizards, varying their exposure to stress during their first year of life. The young were either made to endure attacks from fire ants, or received topical doses of corticosterone dissolved in oil, which causes a spike in their blood corticosterone levels, mimicking their physiological reaction to real-life attacks.

Under stress, the body undergoes a series of physiological changes to help it survive and recover. This results in production of glucocorticoid stress hormones – cortisol in humans, corticosterone in lizards. The hormones interrupt inflammation and suppress the immune system.

Lizards whose ancestors lived in high-stress environments, however, showed a better adaptive response to glucocorticoid, by enhancing immune function instead of suppressing it.

In the long term, having a more robust immune response to stress is more useful in helping lizards deal with a persistent stressor, says McCormick, since stress for a long time or at high intensities comes at a cost, such as reducing growth or compromising reproduction or immunity. McCormick and colleagues still found the results surprising considering their previous works have shown that early life stress in these lizards generally didn’t affect survival, yet stress experienced by their ancestors did.

Researchers plan to study the maternal effects of stress. “Stress experienced by a mother can affect the stress hormones in the yolk of her eggs and can affect stress-physiology, morphology, and behavior of her offspring. We would like to investigate whether maternal effects play a role in the immune differences we saw in this study,” says McCormick.

References

- McCormick, G.L. et al. Population history with invasive predators predicts innate immune function response to early life glucocorticoid exposure. TheJournal of Experimental Biology (2019). | article