1 April 2020

As the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic spreads rapidly, KAIMRC has intensified its research efforts into the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—the virus causing COVID-19—amid efforts to contain it. In addition to shutting schools, universities and suspending international flights and all public events, the government has announced a curfew and temporarily halted umrah.

As of March 29, Saudi Arabia had recorded 1,299 cases of the respiratory disease COVID-19, the largest number of infections reported in a single Arab country, as well as eight deaths, according to the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (WHO-EMRO). Most of the new cases were reported in Riyadh.

COVID-19 is potentially fatal for older people, and those with compromised immunity, underlying illnesses, or existing chronic conditions such as diabetes, or heart or lung disease. Its symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath, varying from mild to severe, and it can lead to pneumonia or organ failure.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

While Saudi Arabia has had extensive experience with another member of the coronavirus family known as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), the level of disruption that SARS-CoV-2 has caused to the Saudi community, and the threat to public health, is unprecedented.

“The 2012 and 2015 MERS-CoV outbreaks in Saudi Arabia led to the shutdown of some hospitals. But, nothing at the time led to a shutdown of community and public places like what we’re experiencing now, because the ways in which novel coronaviruses spread are very different,” says Ahmed Alaskar, KAIMRC’s executive director and associate professor of adult haematology.

Saudi Arabia was the site of the world’s most significant MERS-CoV outbreak, with 2,077 infections and around 773 fatalities, according to WHO. MERS-CoV was first identified in a pneumonic patient in the kingdom in 2012, and broke out again in 2015. Soon after, the kingdom prioritized research into MERS-CoV and poured resources into the study of its epidemiology, and into clinical trials of possible treatments and vaccines.

Alaskar explained that Saudi Arabia has leveraged its expertise with MERS to deal more efficiently with the current outbreak. He warned, however, that the new mutated virus is not only crucially different than MERS-CoV, but it also comes with its own set of challenges.

MERS and COVID-19 manifest similarly, and have many symptoms in common. The pathogens responsible for the diseases probably originated in bats. Both viruses are contracted through close contact with an infected person, with transmission made worse by overcrowding. However, the new virus is more easily transmitted.

“Although MERS-CoV has the more severe impact on patients, with higher fatality rates, COVID-19 is spreading much faster,” says Alaskar.

Projections ICU bed availability across the kingdom vary, but Alaskar explains that a universal issue is that “the healthcare system will not cope with an entire community being sick at the same time.”

In a commentary published in February in the Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health1, Ziad A. Memish, senior consultant for adult infectious diseases at King Saud Medical City, warned that “it will be a huge challenge for healthcare workers to combat both viruses, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.”

The Saudi Ministry of Health reported three more MERS-CoV infections on March 20. Memish recommended that patients are now tested for both MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 simultaneously.

Experience matters

Saudi’s research experience with MERS might provide scientists with clues on the path to understanding the virus, how to contain it, and how to develop diagnostics and potential therapies.

“Prior knowledge of what triggers outbreaks is very important, and previous knowledge of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV can help put us on the right path in our first steps to deal with this novel virus,” says Islam Hussein, formerly a virologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), drug discovery researcher, and senior scientist at Microbiotix.

Hussein adds that this knowledge can help the research community build a picture of coronavirus transmission and how to deal with it effectively.

“Since we’re at a critical point, all the research that was previously done on preventive measures, the vaccines and antiviral drugs that were discovered and shelved but never been pushed to the markets are useful,” he explains.

WHO has announced on March 20 a large multi-country global trial, called Solidarity, that is expected to launch an aggressive, rapid search for drugs by testing four different drugs or combinations at once. Solidarity will also be looking at unapproved medications that showed promise against MERS and SARS during animal studies.

US biopharmaceutical company, Gilead Sciences, has also given several clinical trials access to the investigational broad-spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir — a medication originally developed for Ebola — for experimental use against COVID-19.

Meanwhile, KAIMRC has joined the global race for treatment and vaccines by scaling up research into the novel coronavirus, shifting some of its resources to scrutinizing COVID-19.

Before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China in December 2019, KAIMRC was already working to develop a new vaccine for MERS-CoV that has been tested successfully in camels, and had just been moved to human trials. These efforts are now providing the infrastructure needed by virologists, epidemiologists and infectious disease researchers at KAIMRC and across Saudi Arabia to build knowledge about COVID-19, including tools to study and handle the new virus safely.

“We’ve already started,” says Alaskar. “The only challenge is that we have not yet got enough samples and patients, because we’re currently dealing with a smaller number of patients than those affected by MERS-CoV.”

According to Alaskar, researchers at KAIMRC have successfully isolated the new virus from patient clinical samples and sequenced its whole genome. “Whole genome sequencing would eventually lead to identification of certain targets for therapeutics and for tracking the virus,” he says. “The virus could develop resistance or transform. This way we would be able to track this.”

While international collaborations haven’t been formed, KAIMRC is on the hunt for partners in research within Saudi Arabia.

KAIMRC scientists are already coordinating efforts with other research centres in the country, according to Alaskar, so that clinical trials that were launched into MERS-CoV can be utilized for cases with COVID-19, and the data is shared.

This includes promising research into monoclonal antibodies, synthetic proteins cloned from immune cells and used in drugs that enlist natural immune system functions to recognize and destroy a virus.

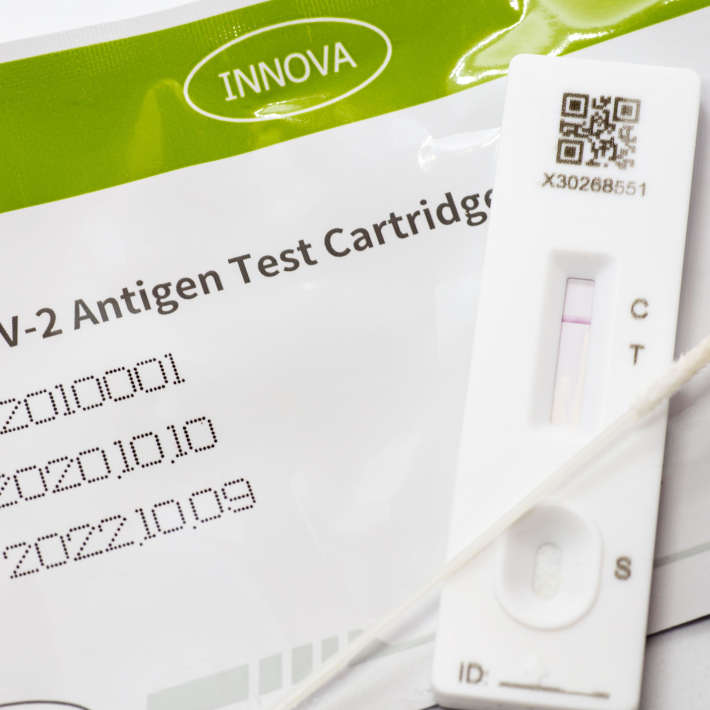

“We also have two rapid diagnostic tests that we're working on,” says Alaskar. “They're still in the early phase. And we're trying to validate these tests. Again, they were developed for MERS-CoV but we're replicating them for COVID-19.”

Despite keen efforts, it is unlikely, however, that a treatment or a vaccine that could potentially turn the tide will emerge soon. It is also unclear whether Saudi Arabia will be further accelerating its research efforts, drug development, or testing of a fast-track vaccine.

“As we see now with this widespread and global pandemic of COVID-19, the whole world is basically trying to shortcut the research, and all government and scientific agencies are under pressure to approve the use of early data to approve vaccines and therapeutics. We have never seen a vaccine developed in four to six weeks, and with no or limited animal testing, and I would say this carries a risk,” says Alaskar. A vaccine typically takes a minimum of one year to be developed.

References

Memish, Z.A. et al. COVID-19 in the Shadows of MERS-CoV in the Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 10 (1): 1-3 (2020) | article