9 February 2019

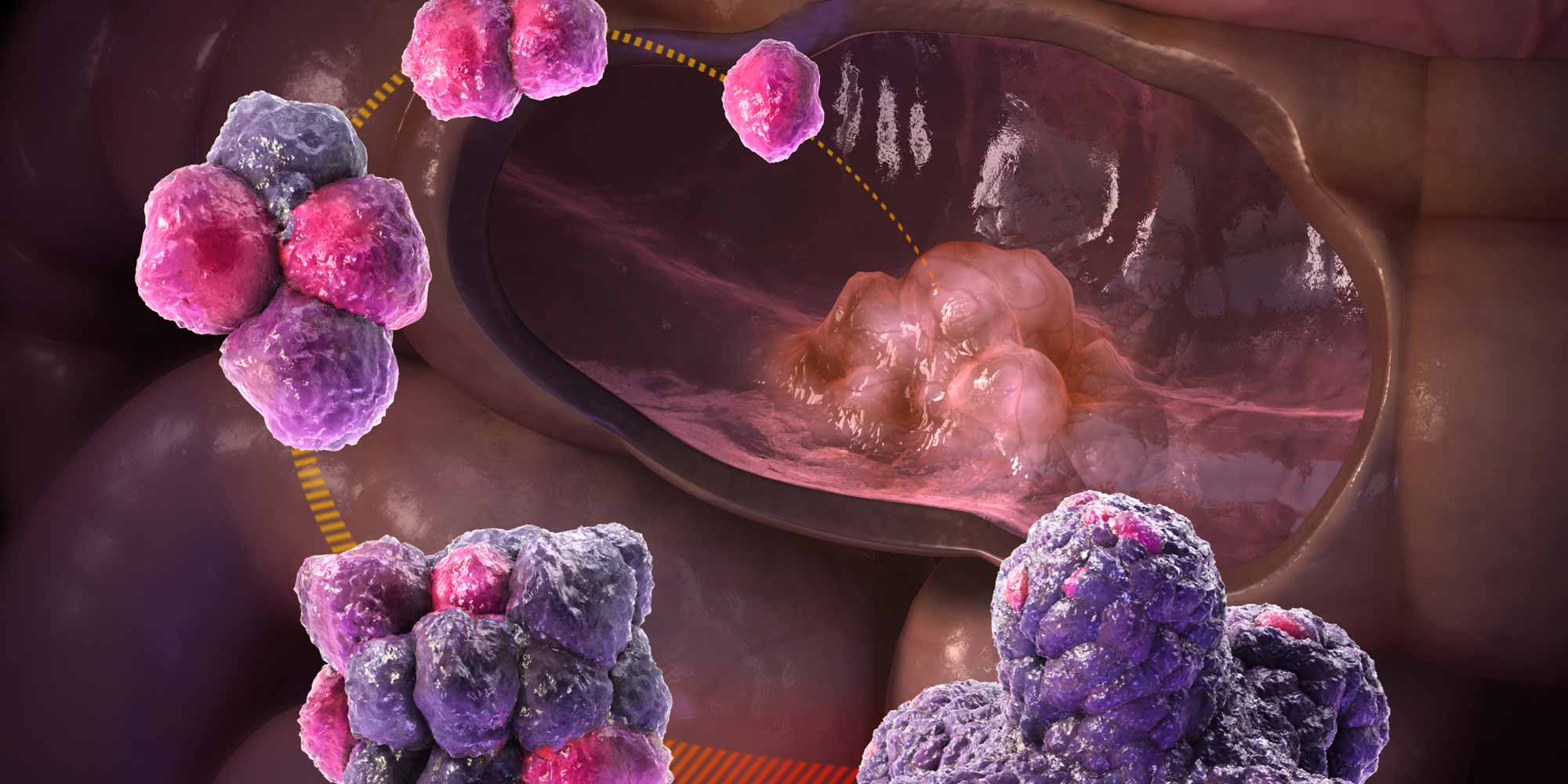

Colorectal, or bowel, cancer is a leading cause of death in adults. The condition is difficult to treat because the makeup and development of bowel tumours differs from patient to patient. A generic approach often fails.

Scientists from the University of Utrecht in The Netherlands, and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, propose a more personalized approach to bowel cancer starting with the molecular composition of the tumour itself. Their research reveals features specific to each cancer patient, while also highlighting common molecular signatures of the disease.

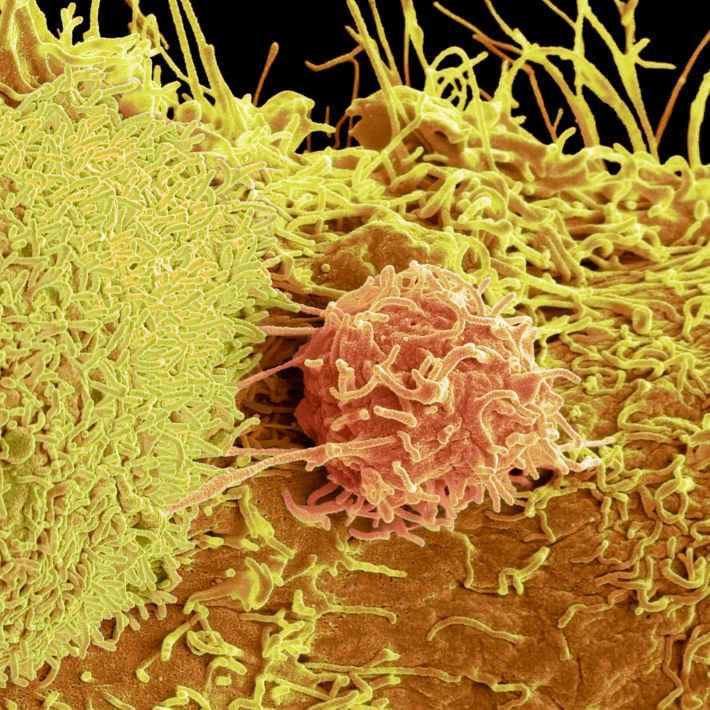

The study makes use of a new technology known as ‘organoids’, in which a small tissue sample can be grown in the lab into a long-lived, simplified, miniature organ, containing all the cell types of the original tissue. Co-author Hans Clevers explains that the bowel was “where we first worked out the procedure to establish organoids.”

The researchers generated organoids from tumours and healthy tissue in seven bowel cancer patients. They then examined the proteins found in each organoid— its ‘proteome’—comparing these between patients, and between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues.

Of the thousands of proteins identified, around 400 differed between tumour and healthy organoids from each patient. This was far greater than the number of active genes differing between the same tissues, emphasizing the useful additional perspective provided by the proteome.

The team next identified proteins implicated in tumour development. For instance, one patient’s tumour organoid had diminished levels of a protein, MSH3, which is responsible for repairing mistakes in DNA. MSH3 deficiency can cause the genome to become unstable, and has already been associated with colorectal cancer.

In fact, many proteins are implicated in genome stability, and deficiencies in any of these may cause cancer. The type of instability —what part of the genome is affected— can be crucial to a patient’s response to treatment. Thus, knowing which proteins are diminished may help provide targeted treatments and improve chances of survival.

The levels of other proteins, around 300, were varied in the tumour organoids of all patients, and may prove to be valuable markers for colorectal cancer.

Overall, the organoid technology explored by the Utrecht-Oxford team represents a marked advance over previous methods for exploring treatment options, and is less intrusive than repeated testing on actual patients. Clevers reports that the technique is already being trialled in a range of other cancers including pancreatic, prostate, breast and ovarian cancers

References

- | Cristobal, A., van den Toom, H. W. P., van de Wetering, M., Clevers, H., Heck, A. J. R. et al. Personalized proteome profiles of healthy and tumor colon organoids reveal both individual diversity and basic features of colorectal cancer. Cell Reports 18, 263—274 (2017). | article