10 February 2019

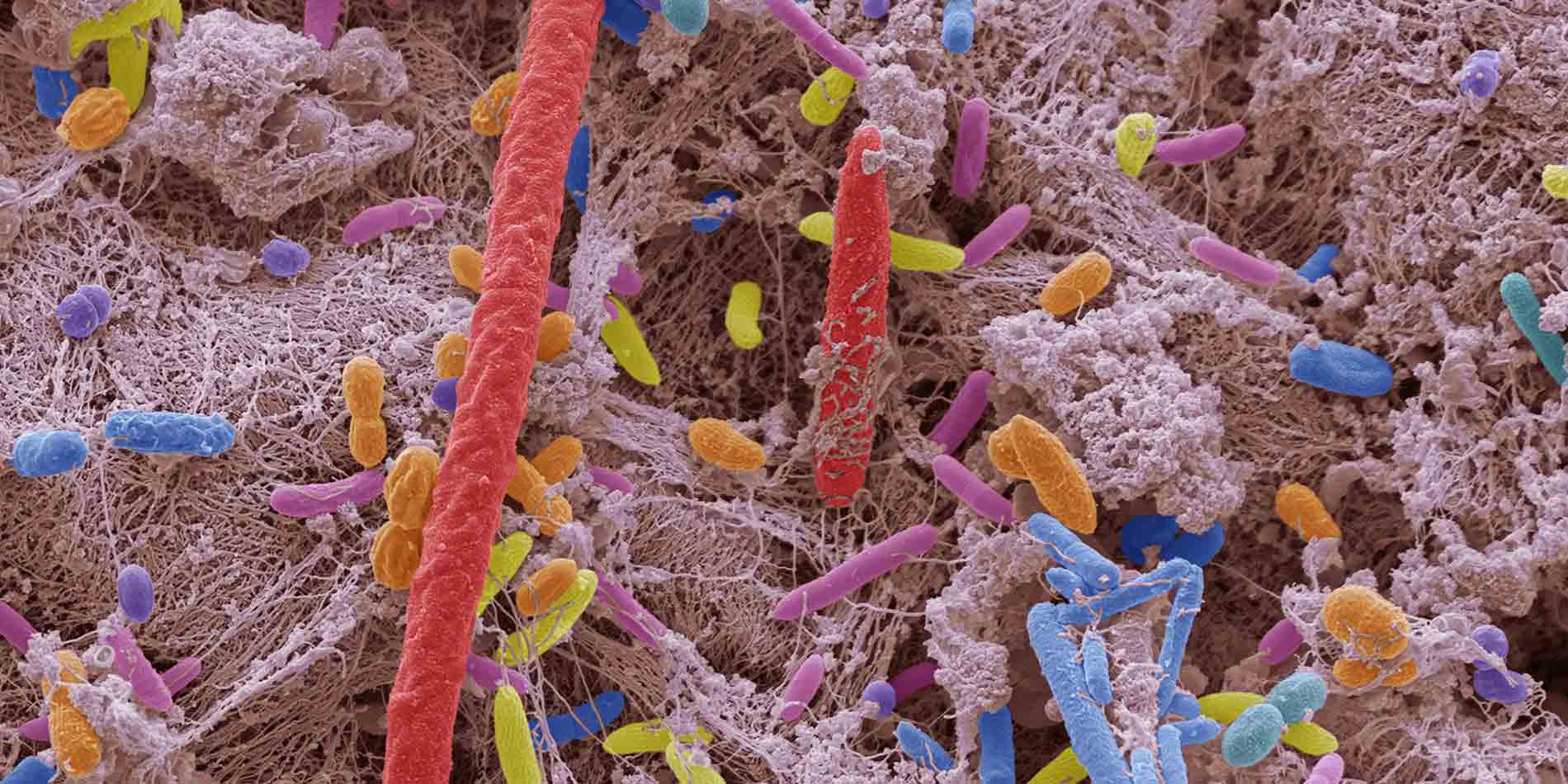

The body harbours many diverse communities of bacteria that play a prominent but poorly understood role in health and disease. A recent survey of samples from hundreds of volunteers offers a wealth of valuable insights into the composition, function and dynamics of this internal ecosystem.

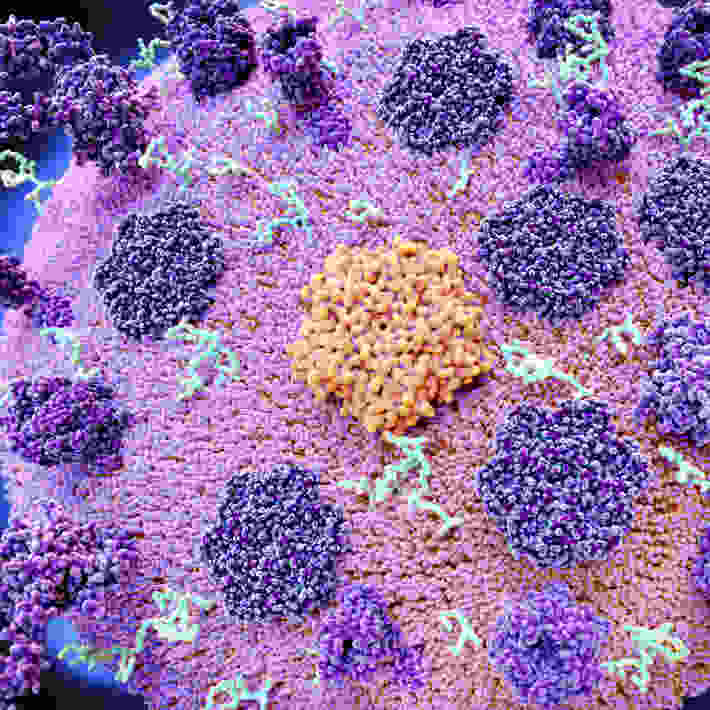

In 2012, the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) released its first dataset: a survey of bacteria collected from the mouth, gut, genitals and other tissues of 242 healthy volunteers. A follow-up study from HMP researchers led by Curtis Huttenhower of The Broad Institute in the United States delves even deeper. By drawing on improved analytical tools and samples collected from 265 North American donors at multiple time-points, Huttenhower’s team has obtained a more extensive and dynamic view of the microbiome.

In total, they examined 1,630 ‘metagenomes’ derived from microbial populations isolated from six different body sites. The researchers found that people generally maintain relatively stable bacterial communities over time, with far greater differences seen between individuals. However, they did observe some dynamic scenarios. For example, there is apparently regular fluctuation among Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes bacterial populations dwelling in the intestine, indicating that levels of these species may prove less useful as indicators of microbiome-associated health.

Huttenhower and colleagues identified 54 additional species of bacteria in their dataset relative to the first HMP study. They were also able to identify microbes that preferentially dwell in certain parts of the body, and to home in on biological functions that tend to be broadly shared across species versus those that are more common in certain physiological environments. For example, bacteria living in the gut were far more likely than those dwelling elsewhere to produce enzymes that break down plant-derived sugars, and to release chemical compounds that protect the intestinal lining.

By employing sophisticated new algorithms for DNA sequence analyses, the researchers were able to identify millions of bacterial genes present in each body site studied. However, their analyses indicate that the current HMP census is far from complete. The authors note that future microbiome surveys should strive for greater ethnic, geographic and environmental diversity, and be coupled with a deeper analysis of health and lifestyle factors that may shape our inner ecosystems. “To rationally repair a dysbiotic microbiome, it is necessary to deepen our understanding of the personalized microbiome in human health,” they conclude.

References

- Lloyd-Price, J., Mahurkar, A., Rahnavard, G., Crabtree, J., Orvis, J. et al . Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 550, 61-66 (2017) | article