11 August 2016

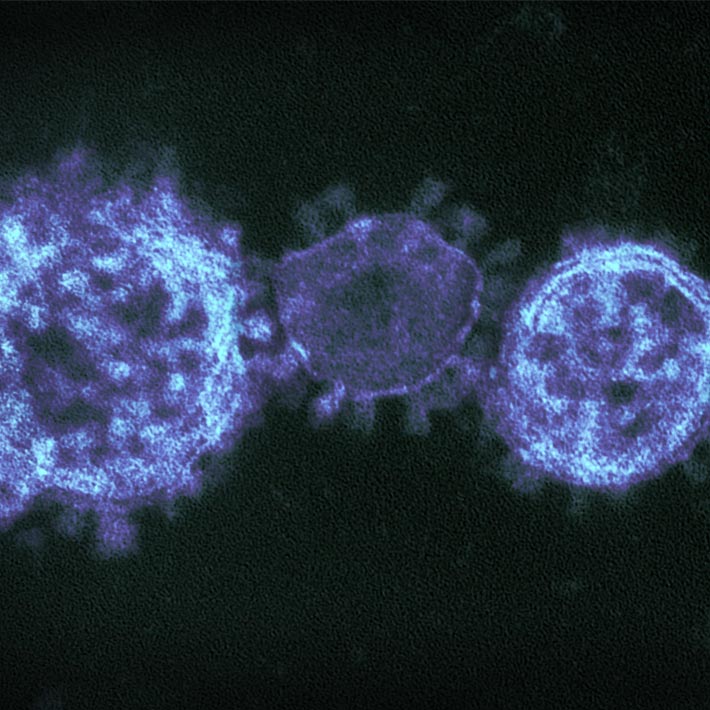

Researchers have revealed how the hepatitis C virus uses a special structure to organize its reproduction in host cells and evade their immune response.

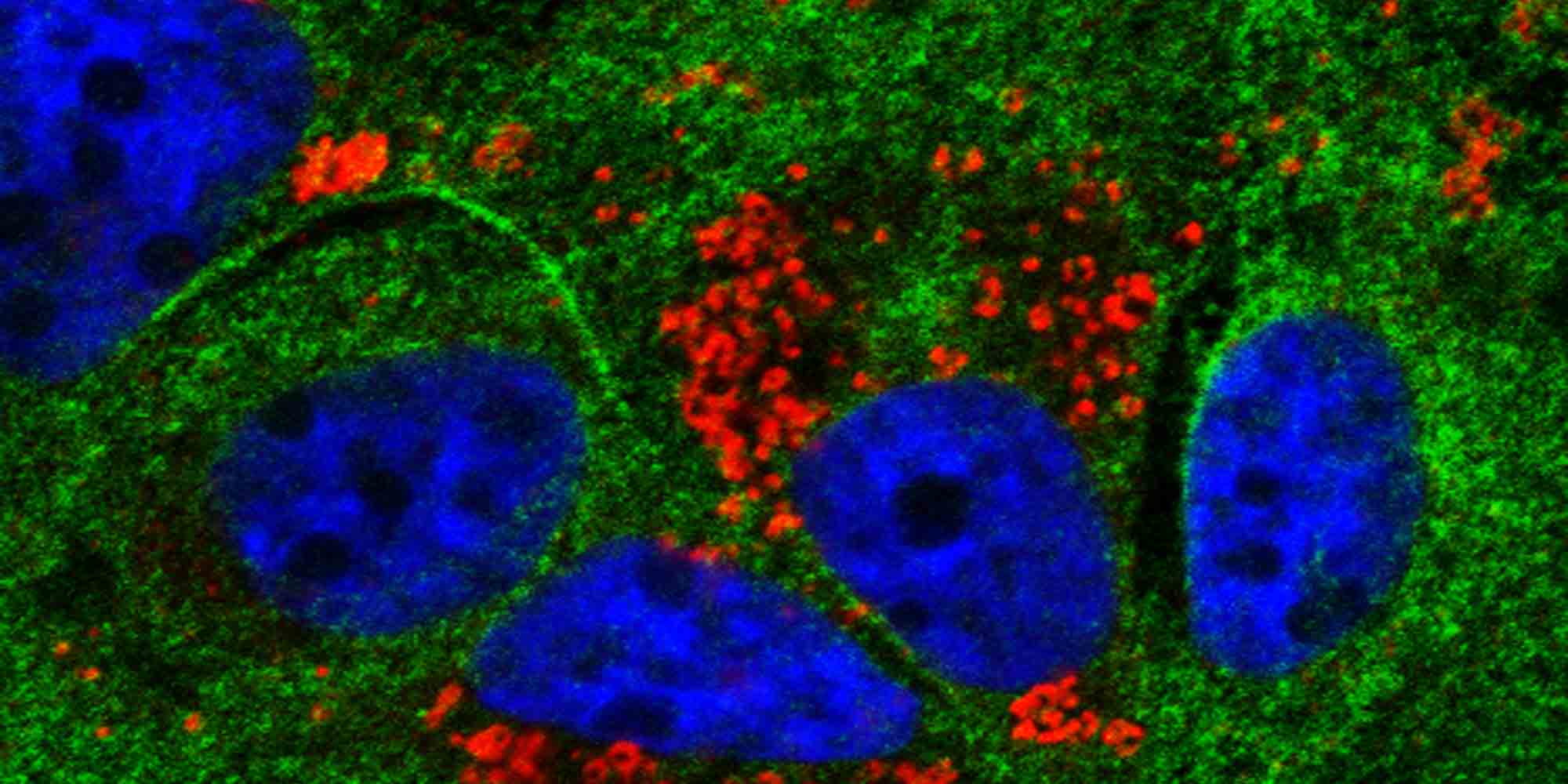

The virus, which affects roughly 170 million people worldwide, rearranges the host cell’s internal membranes into a structure called the membranous web.

Researchers had already shown that some viral proteins include markers for transport into the nucleus, called nuclear localization signals. Michael Joyce, a researcher at the University of Alberta, suspected that hepatitis C’s membranous web was co-opting a structure in the nucleus that controls traffic to and from it, called the nuclear pore complex (NPC).

To test this idea, Joyce teamed up with his colleague Richard Wozniak, whose lab at the university focuses on the NPC. In previous studies published in 2013 and 2014, the team showed that hepatitis C hijacks the NPC and that several of the virus’s proteins have functioning localization signals1,2.

“This third paper brings the idea back almost full circle and ties it to the innate immune response,” says Joyce. The team demonstrated that the membranous web employs components of the NPC to control access to its internal compartments. They also found that key viral proteins were isolated within the membranous web while host proteins that activate the immune response were kept outside. The membranous web thus serves as a gated community for vulnerable viral components, creating space for them to interact undetected by the cell’s immune machinery3.

Next, the team tested whether the addition of a nuclear localization signal could get the immune-response proteins past the gatekeeper. Proteins with the signal were carried into the membranous web, where they could detect and recognize various viral components and activate the cell’s immune machinery.

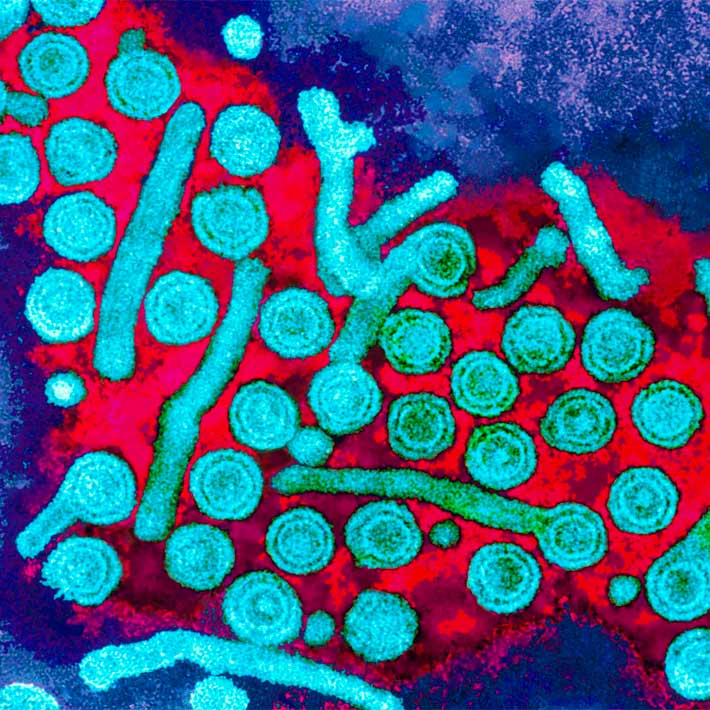

The team showed that the same mechanism is at work in the group of viruses hepatitis belongs to, which includes the dengue and Zika viruses, though the details differ. “This is a new way of looking at how viruses work,” says Joyce. “I hope there will be many more studies elucidating these mechanisms in the life cycles of different viruses.”

References

- Neufeldt C.J., Joyce M.A., Levin A., Steenbergen R.H., Pang D., et al. Hepatitis C virus-induced cytoplasmic organelles use the nuclear transport machinery to establish an environment conducive to virus replication. PLoS Pathogens (2013) | article

- Levin A., Neufeldt C.J., Pang D., Wilson K., Loewen-Dobler D., et al. Functional characterization of nuclear localization and export signals in hepatitis C virus proteins and their role in the membranous web. PLoS One (2014) | article

- Neufeldt, C.J., Joyce, M.A., Van Buuren, N., Levin, A., Kirkegaard, K. et al. The Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Membranous Web and Associated Nuclear Transport Machinery Limit Access of Pattern Recognition Receptors to Viral Replication Sites. PLoS Pathogens (2016) | article