17 May 2020

When multiple treatment regimes exist for a medical condition, deciding on the most effective course of action is crucial. A recent study by the Saudi Critical Care Trials Group may prevent unnecessary medical intervention by showing that critically ill patients on drugs to prevent deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) don’t benefit further from mechanical compression therapy.

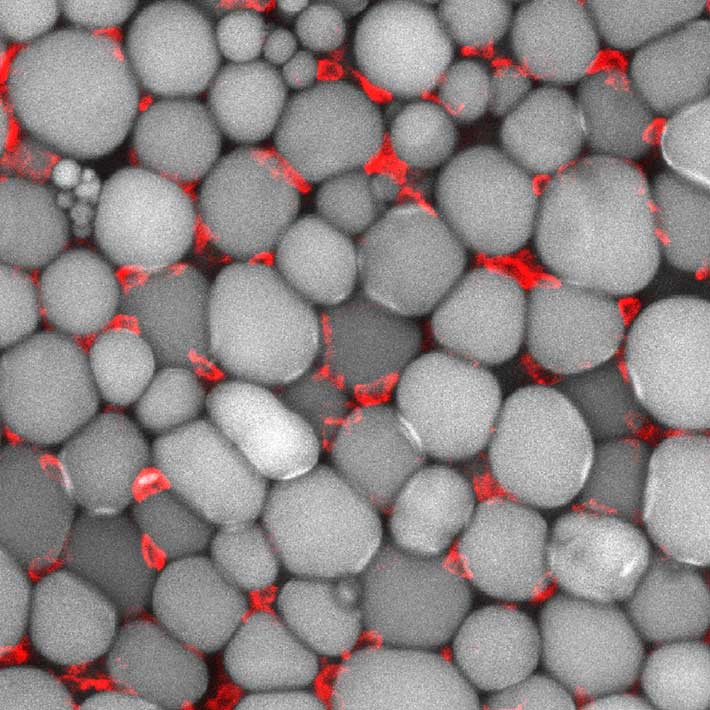

DVT occurs when blood clots in veins deep within the body, usually the legs. The disease can occur as a result of prolonged inactivity, such as when on long-distance flights, or during hospital stays. When the legs are still for extended periods, muscles contract less, leading to less blood circulation and an increase in the likelihood of clots. DVT can cause swelling, redness and/or pain, and a life-threatening complication called pulmonary embolism, when a clot travels to the lungs and causes potentially fatal lung damage or heart failure.

People hospitalized for lengthy periods are at a greater risk of DVT, critically ill patients are a particularly vulnerable group — with an incidence rate “as high as 25%” in some populations, says Yaseen Arabi, of Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, who led the group’s study. This makes them an ideal population to test the effectiveness of DVT-preventative therapies.

The study followed 2,003 patients at Intensive Care Units across four countries. The patients were assigned to one of two groups. The first group received heparin, a standard pharmacological agent in the prophylaxis and treatment of blood clots. Alongside heparin, the second group also underwent Intermittent Pulmonary Compression, in which the legs are placed in inflatable sleeves which intermittently compress the legs to promote blood flow.

After 28 days, researchers found no significant difference in DVT incidence between the two groups, indicating that IPC didn’t provide any additional benefit to patients already taking heparin. The study also investigated secondary health indicators, such as pulmonary embolism and death rates. The addition of IPC had no influence on these outcomes.

“IPC was found to be helpful in previous studies involving patients who were not on pharmacologic prophylaxis,” explains Arabi. “Our study addressed specifically whether adding IPC had added benefits, and the study showed it did not.”

While this might be seen as a disappointing result, the knowledge gained from the study can greatly benefit patients undergoing DVT prophylaxis. IPC is cumbersome, reduces patient mobility, and can cause skin injury. Knowing that IPC won’t provide extra benefit, patients on pharmacological prophylaxis for DVT can preserve their quality of life by avoiding unnecessary treatments.

References

Arabi, Y.M., Al-Hameed, F., Burns, K.E.A., Mehta, S., Alsolamy, S.J. et al. Adjunctive Intermittent Pneumatic Compression for Venous Thromboprophylaxis. New England Journal of Medicine 380, 1305-1315 (2019). | article